Centuries ago, during Bernie Sanders’s first presidential run, US democratic socialist types got really excited about French socialist André Gorz’s concept of “non-reformist reforms.” Merely reforming the capitalist system would be a sorry goal for a resurgent US socialist movement. And there was no question that campaign promises like Medicare for All were, in some sense, reforms—after all, they were campaign promises. But, the thinking went, such proposals were so far left compared to typical political discourse that they qualified as non-reformist reforms. Reforms that “move an ever-larger share of the economy away from the profit motive,” “contribute to a more just, peaceful situation internationally,” or “promote community, solidarity, care, and inclusion” were, we were told, not bad, inadequate capitalist reforms but in fact, good, proto-socialist non-reformist ones by virtue of the left-ish content.

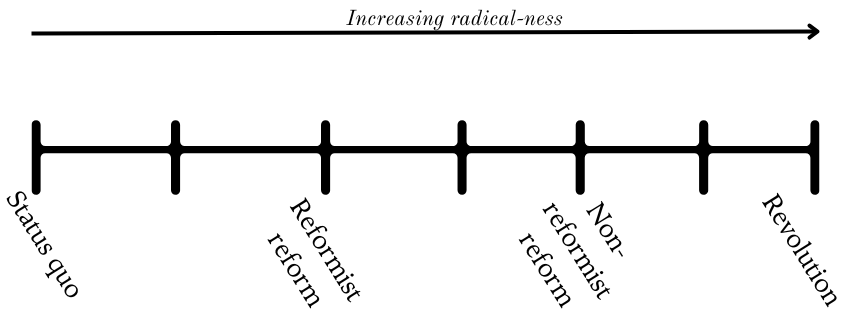

We can reconstruct the assumptions underlying such thinking something like this. Imagine a scale from 0 to 100, with 0 being the maintenance of the status quo and 100 being revolution.

A 25 on this linear scale might be a (bad, inadequate, illusory) reformist reform, but something a bit farther along (say, 75?) would be a good, non-reformist reform. To differentiate the actually non-reformist from the deplorably reformist reform, we just need to analyze its content and plot its position on the status quo-to-revolution axis:

The first problem with this framework is that there’s no way to qualitatively distinguish between the two types of reform. Differentiating efforts to effect structural change from window-dressing for the continuation of exploitation is question of crucial importance for oppositional social movements. But any number of milquetoast Democrats could recite platitudes about “community, solidarity, care, and inclusion” in a campaign speech. And we’ve all spent a year being gaslit by establishment Dems proclaiming that they’re “contributing to a more just, peaceful situation internationally” by funding repeated mass murder. Would national single-payer be a less capitalist form of healthcare provision than Obamacare? Sure. But what makes the one reformist and the other not?

I know that it probably seems like I think that “non-reformist reforms” is an irredeemably broken concept, and I actually don’t. The second problem with the kind of thinking I’ve outline above is that this understanding of non-reformist reforms is actually diametrically opposed to what the term originally meant.

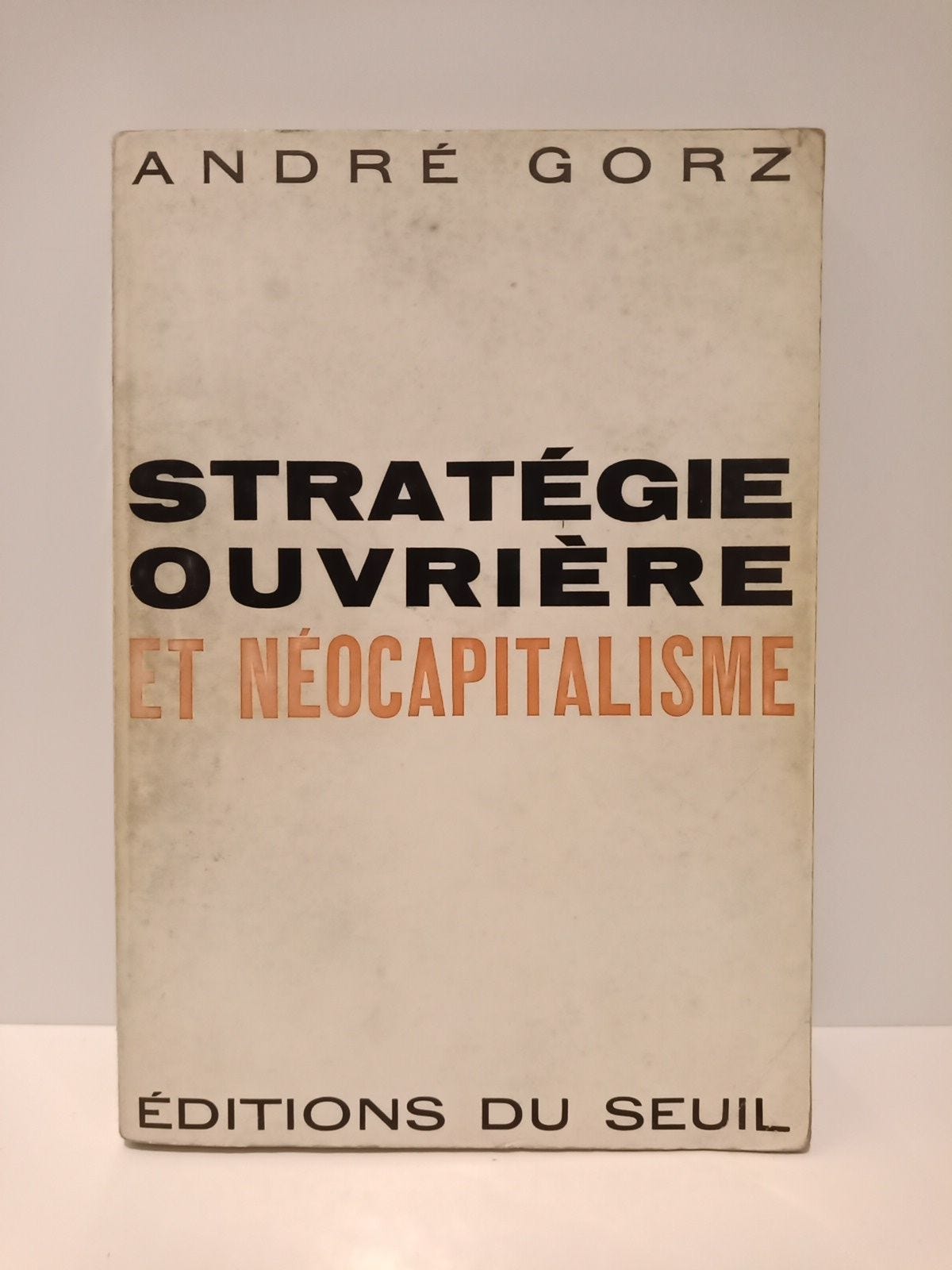

That’s right: the crazy thing is that André Gorz’s 1964 A Strategy for Labor (which you can read for free here) explicitly argues against the idea that a proposed reform magically becomes non-reformist simply because it’s more progressive than the alternative. That’s not a non-reformist reform, that’s just a more progressive reform.

Tuition forgiveness, Medicare for All, defunding the police… none of these become quasi-revolutionary just because they’re farther to the left. “If the strategy of intermediate goals is trapped by this illusion,” Gorz writes, “it will fully deserve the labels of reformist and social-democrat which its critics give it.” Yes, Gorz also uses social-democratic as a pejorative—sorry, DSA members!

In fact, no policy that the capitalist state could even conceivably implement counts, for Gorz, as a non-reformist reform. His non-reformist reforms are like rhetorical trojan horses. They look at first glance like any other reasonable political demand we might express to the state. On closer inspection we find that, despite their reasonableness, they are demands it would be impossible for the state to fulfill. They look like proposals for reform, but are non-reformist in that they can only be accomplished by autonomous social movements. In Gorz’s words:

“The struggle for partial autonomous powers and their exercise should present socialism to the masses as a living reality already at work, a reality which attacks capitalism from within and which struggles for its own free development.”

We might say that an actually non-reformist reform is simultaneously reasonable and impossible. Its apparent reasonableness is what allows it to be snuck into political discourse, while the impossibility of it being realized by the capitalist state is what makes it essentially revolutionary regardless. This might sound quite complicated, but I’d bet that you’re familiar with a few examples of such demands already. For example:

Abolish the police

Abolish the police has the same structure as “defund the police,” “support the police,” “give mine-resistant armored personnel carriers to the police” … any number of policy changes one could support in regards to the police. It therefore looks like a reform. But when you think about it, abolishing the police means abolishing the government. Abolishing the police who enforce laws is tantamount to rendering obsolete the politicians who write them and the judges who interpret them. A city council that actually abolished its police would be effectively abolishing itself as a political entity. It would have to be rebellious social movements exercising their “autonomous powers” who would force an end to policing as an institution.

Take Back the Night

Take Back the Night events protest misogynist and queerphobic violence, particularly the victim-blaming that discourages non-men from inhabiting public space at night, “for their own safety.” Since the 1970s, yearly Take Back the Night actions have been held in cities, towns, and college campuses. Demanding that a university administration institute policies so that the female half of a student body doesn’t face significantly elevated risks of random risks of random, horrifying violence is an extremely modest, reasonable reform to demand. It’s also probably impossible for any set of policies on a particular campus could achieve this goal given the heteropatriarchal society surrounding it and everyone in it. That’s not to say that schools or municipalities can’t pass less horrifying policies, but unmaking a culture of patriarchal violence results from mass feminist mobilization itself.

Ceasefire now

I know this isn’t a universal position, but I’m just going to say it: I think there’s basically a 0% chance that the United States government willingly imposes significant restraints on the slaughter in Palestine. Not only is the pro-Israel lobby comically influential, but unconditional support of the Israeli regime has been a cornerstone of US foreign policy doctrine for the greater part of a century. I don’t think anyone even remotely close to the centers of power think they can turn against the Israeli state without the American empire, US GDP, and most certainly their career getting immediately wrecked.

What I’m saying is that I think there’s literally no amount of letter writing, petition signing, permitted protest organizing, truth-to-power-speaking that would cause the American elite to stop sending unlimited money to keep murdering Palestinian refugees indefinitely. I recognize that this analysis is, indeed, depressing as hell. But I want to be very, very, very clear: this in no way means we shouldn’t demand a ceasefire and the absolute liberation of Palestine. A ceasefire and end to Israeli settler-colonialism is a modest, reasonable, urgent, and necessary reform that any non-grotesque person ought to be fighting for by any means necessary. That just might involve disempowering the United States regime.

If what it takes to get the richest country in human history to stop barbecuing families sheltering in the bombed-out remains of hospitals is launching the Pentagon straight into the sun, well…

In conclusion

I think there’s an idea that espousing radical politics means formulating especially expansive demands: six day weekends and a pony for every American! (This is not a dig at Vermin Supreme, an underappreciated national hero and the only exception to my anti-voting politic.) But I’ve become really intrigued by what I understand as (actual) non-reformist reforms: commonsensical demands that would nonetheless, because of the radical inadequacy of the capitalist state, require revolutionary transformation to achieve. When we articulate authentically non-reformist reforms, we’re communicating the necessity of revolutionary change. In Defying Displacement, I argue that the seemingly minor reforms necessary to truly end gentrification would in fact require uprooting contemporary capitalism in the form of what I dub the gentrification economy—and that this is all the more reason to organize against displacement. Because we have, as has been said, a duty to win.

If you enjoyed this piece, or hated it but would like to hate-read similar content in the future, subscribing, sharing, liking, and commenting are all important ways to support.

I can’t wait until election season has come and gone in the US and so called Canada. Listening to so called progressives talk about how “it’s the most important thing we can do to fight fascism” and “if we vote for the lesser of two evils then we can at least work with that party!” Is literally a brain disease and I feel like it’s eating me from the inside.